Intro

A little over three years ago, I reviewed TRP’s first attempt at a mountain bike drivetrain, the TR12 shifter and derailleur. I came away thinking that the system showed promise but needed more refinement, and that it would need to eventually be a complete drivetrain — not just a shifter and derailleur — to be a legitimate contender to SRAM and Shimano’s duopoly atop the mountain bike drivetrain market.

TRP clearly agreed, and the Evo 12 is their response. I’ve been using a single Evo 12 drivetrain across three different bikes since last fall, and now it’s time to weigh in on how TRP has done with their first complete drivetrain.

Setup & Maintenance

Installing the Evo 12 drivetrain is pretty typical for a mechanical 1x setup, with a few minor differences in the details. I won’t cover every step here, just a few noteworthy bits; check out TRP’s instructions if you want the full rundown.

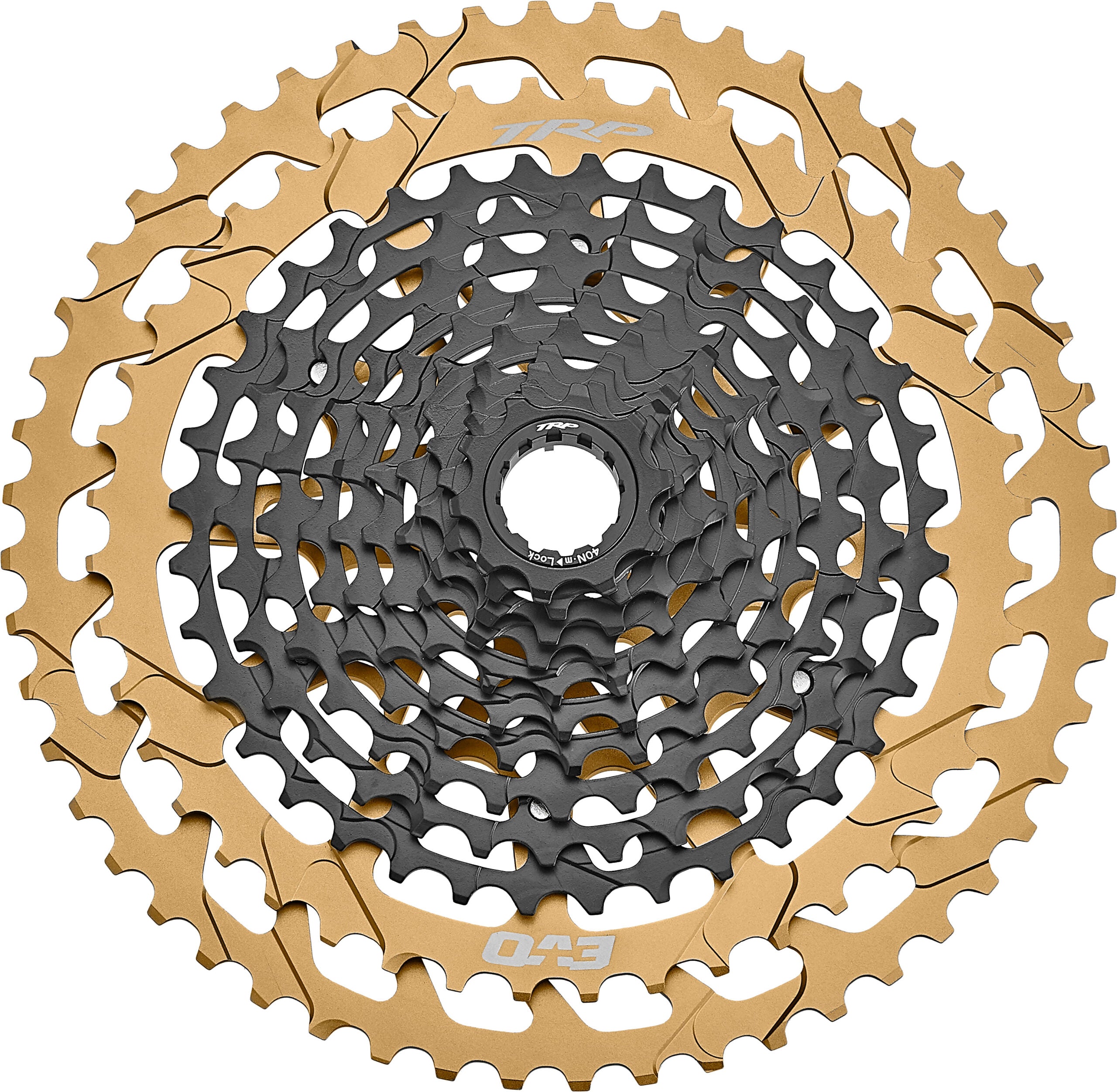

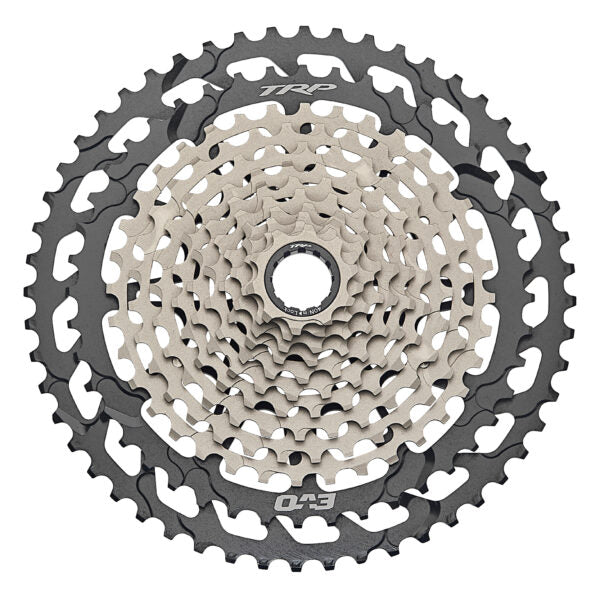

The TRP cassette uses a Microspline driver, but unlike Shimano’s Microspline cassettes, it’s a single piece so there aren’t any separate cogs and spacers to line up. (The largest two cogs are machined from a single piece of aluminum, and the remaining ones from a block of steel; the two halves are bolted together to make the full cassette.) Consequently, TRP’s cassette is quicker / easier to install and won’t chew into aluminum freehub bodies (though I haven’t had major issues with Shimano 12-speed cassettes there, either). SRAM’s XD cassettes are also one-piece affairs, but they take more effort to tighten and remove due to their interference fit on the freehub.

Compared to SRAM’s mechanical derailleurs, I have found the Evo 12 derailleur to be a little more sensitive to B-tension adjustment when trying to achieve optimal shifting performance. However, unlike SRAM’s mechanical offerings, I haven’t had any issues with the Evo 12’s B-tension screw backing itself off while riding.

TRP’s guidelines for how to set it seem more or less accurate, but there’s a two-millimeter range within their recommended window, and I found a marked difference in shifting performance even within that range. If you’re finding the Evo 12’s shifting to be a little imprecise (particularly in the lowest few gears), experiment with the B-tension a little. (In my experience, worse downshifting performance indicates too little B-tension and vice versa.)

I’ve installed the Evo 12 on three different bikes now and needed to do a bit of fine-tuning on all three, but it’s stayed put and continued to work great once I found the right setting. Just remember to release the Hall Lock lever when making adjustments, and tighten it down again after.

The Evo 12 derailleur also features a cage release function that fully decouples the cage from the clutch and spring to make wheel removal and installation easier — it’s a different way of accomplishing the same goal as SRAM’s cage lock button. The Evo 12’s mechanism requires you to push down on one tab and pull out on another to prevent accidental release of the cage. I found the operation to be a little unintuitive the first few times I tried it, but I quickly got the hang of it and have come to really like the setup. It’s easy to do one-handed and does a nice job of getting the cage out of the way.

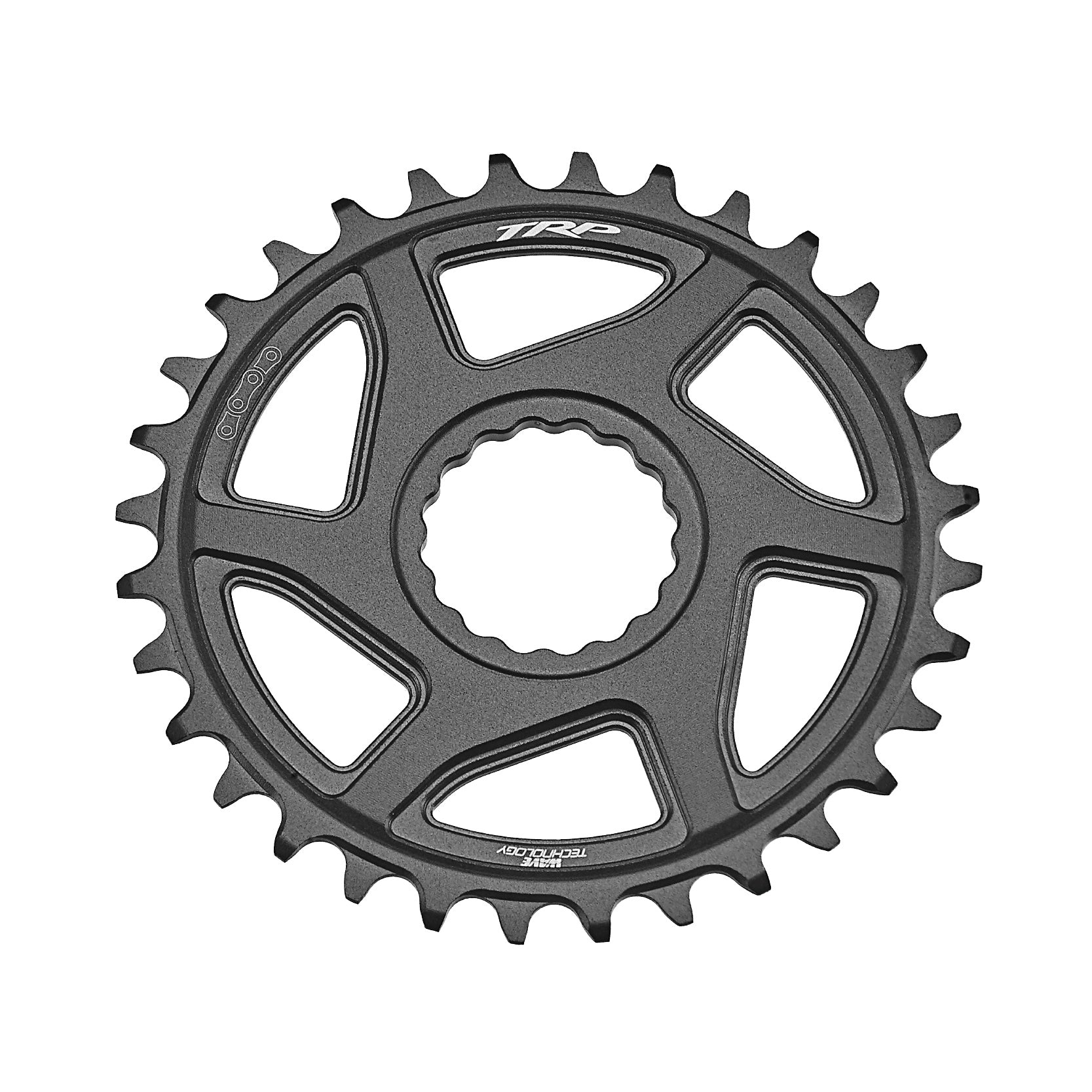

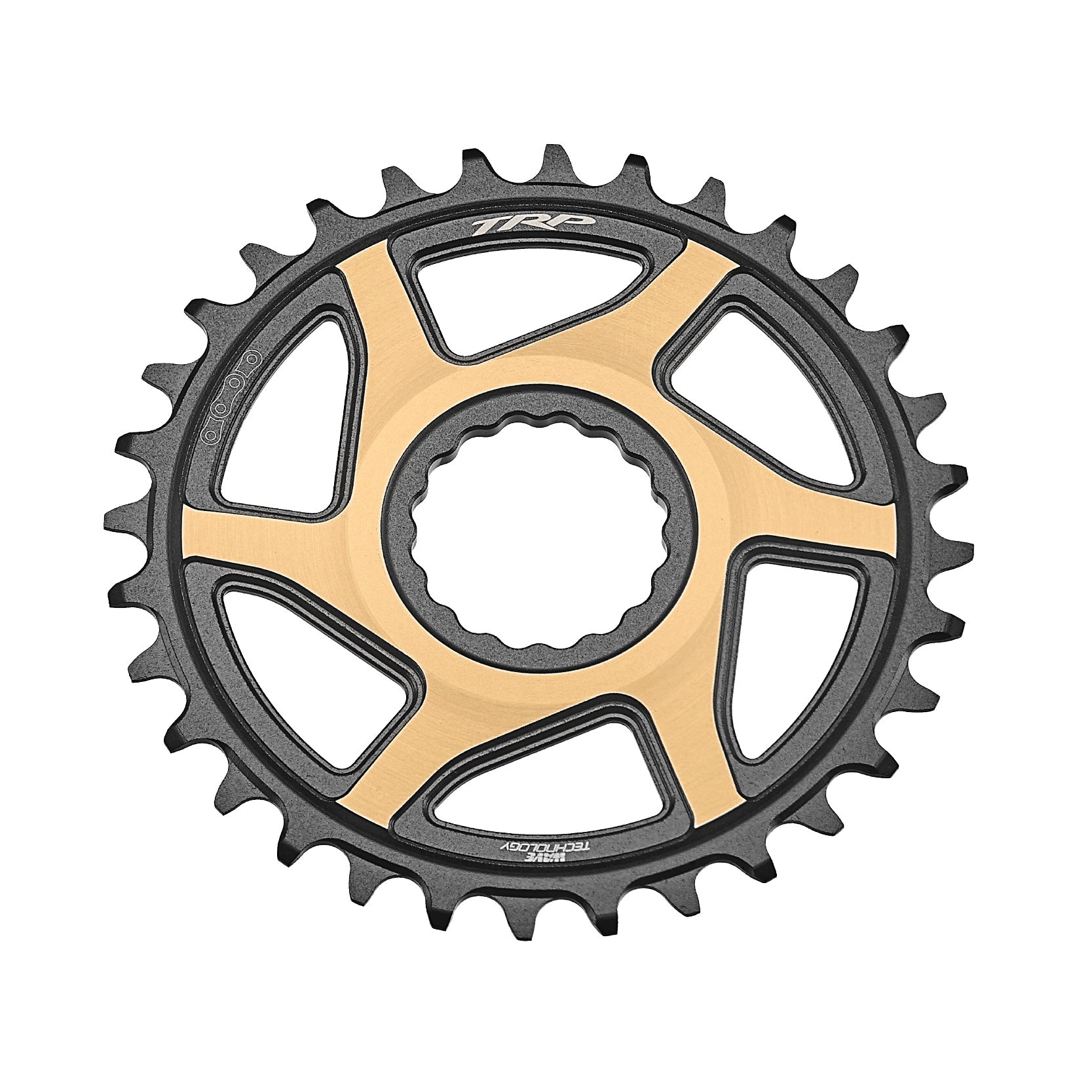

The installation procedure for TRP’s crank and bottom bracket is essentially the same as that of a Race Face Cinch crank, down to the use of a 20-spline bottom bracket tool for the chainring lock ring. The crank fixing bolt uses a 10 mm Allen wrench, and while it’d arguably be nice for it to be 8 mm since those are more commonly found on multi-tools for a trailside fix, it’s pretty tough to achieve the required 50 Nm of torque with one anyway. The self-extracting bolt works nicely, with none of the sticking issues that have plagued SRAM’s DUB cranksets.

On-Trail Performance

I’ve been very happy with the shifting performance of the Evo 12 drivetrain — it’s a worthy competitor for SRAM and Shimano’s high-end mechanical offerings. It’s also a big improvement over the original TR12, TRP’s first stab at a mountain bike drivetrain.

The Evo 12 drivetrain shifts accurately, smoothly, and fairly well under power as well, though it’s not quite as smooth as Shimano’s 12-speed systems if you’re fully on the gas; let off just a little bit, and the Evo 12 does really nicely.

The Evo 12 also does a notably good job of downshifting a whole bunch of gears at once. On a lot of mechanical drivetrains, you can dump a pile of gears at once through the shifter, but it can be easy to get the chain to skip on the cassette and not shift very cleanly when doing so. SRAM’s Transmission moves more deliberately and does each individual shift, rather than going straight to the final gear, which is great for shifting accuracy but takes longer. The Evo 12 isn’t impervious to skipping if you try to drop four or five gears at once, but it’s been a bit better overall than either SRAM or Shimano’s mechanical drivetrains.

The ergonomics of the TRP Evo 12 shifter are a particular high point for me. The paddles are well-positioned (the downshift one is adjustable), their shapes work really well for me, and their action is an excellent combination of being quite light while still having clear, positive clicks to indicate each shift. Folks who find Shimano’s 12-speed shifters to take more force than they’d like (something I’ve noticed not minded too much) should take particular note — the Evo 12 shifter has the lightest action of any 12-speed mechanical shifter I’ve tried to date.

I’ve also gotten along fairly well with the cassette gear ratios that TRP has chosen. SRAM’s original 52-tooth Eagle cassettes drove me nuts with the massive jump between second gear (42 teeth) and first (52 teeth); the TRP one has a notably big jump between second and third gears (44 and 36 teeth, respectively) that I’d love to see evened out a little bit but it hasn’t bothered me too much (TRP’s fourth gear has 32 teeth, making for a pretty small jump between third and fourth gears).

(For what it’s worth, Shimano’s ratios are still my favorite out of the mainstream 12-speed options. They get slightly tighter in the lowest handful of gears, where I’m doing the bulk of my climbing and care most about maintaining a specific cadence, and they offer a tighter-ratio 10-45 tooth cassette if you don’t need the full 10-51 tooth range. But both the TRP Evo 12 and SRAM T-Type cassettes are fine in my book, too.)

I’ve been generally happy enough with TRP’s carbon crank, too. It’s reasonably light for a fairly burly carbon crank, coming in a touch heavier than the Race Face Era, for example (538 g w/ chainring vs 495 g), but TRP’s is stiff enough for my taste and hasn’t given me any trouble. Its Q-factor is a touch wider than I’d prefer, though that’s also true of a whole lot of other modern MTB cranks, including the Race Face Era and SRAM’s T-Type offerings. TRP doesn’t publish a Q-factor for the Carbon Cranks, but it feels close to that of the standard T-Type cranks (which are 174 mm).

The Evo 12’s mode adjustment switch is a neat touch, too — it toggles the shifter between being able to downshift up to five gears at once or limiting it to a single click. I personally haven’t been inclined to use the single shift mode, apart from briefly trying it as a curiosity, but it’s there if you want it (it’s probably particularly useful for folks on eMTBs). I haven’t had any issues with it accidentally changing positions or anything like that.

Durability

Overall, the Evo 12 drivetrain has fared very well, including surviving a whole lot of miles through the wet winter months here in Western Washington. The cassette is showing impressively little wear; the derailleur is straight and still shifting well; the shifter hasn’t developed any noticeable slop; and the shift paddles haven’t gotten appreciably crunchier — they’re still quite smooth and light.

I did need to slightly tighten up the clutch in the derailleur partway through my testing, but it’s easy to do (much more so than on the original TR12 derailleur). And I’m glad that it is adjustable, unlike SRAM’s 12-speed offerings. On the Evo 12, you just need to remove the three bolts that attach the cover over the cage pivot and tighten the clutch screw a touch — basically the same procedure as Shimano’s 12-speed derailleurs. Work in increments of a small fraction of a turn — a little goes a long way.

I wasn’t having major issues before tightening the clutch, but the amount of chain slap and noise I was getting gradually increased as it wore in. Tightening the clutch helped considerably, but the Evo 12 is still a tiny bit louder than a really dialed Shimano 12-speed setup. The Evo 12, though, is a big improvement over SRAM’s Eagle (non-T-Type) derailleurs after those have worn in a bit, especially the AXS versions; the Evo 12 and Transmission derailleurs feel about on par there.

I have found the recommended KMC X12 chain to wear substantially faster than SRAM and Shimano’s higher-end offerings, though, to be fair, the X12 is also available for under $30, and comparably-priced options from the S-brands are far less durable than those brands’ high-end variants (e.g., SRAM X01 and Shimano XTR). When the KMC chain that TRP supplied for testing wore out, I tried a SRAM X01 Eagle (non-T-Type) chain that I had on hand and found it to work at least as well as the standard KMC chain. If anything, the SRAM chain might be a tiny bit quieter and smoother shifting, but both work pretty well.

I’ve also found the TRP chainring to be a bit quicker wearing than average. It’s still hanging on after about eight months of fairly regular use, but its chain retention has suffered to the point that it really needs an upper guide to keep things in check. The TRP cranks use a Cinch chainring mount, though, so a variety of third-party options are available.

And the cranks themselves have held up well. They’ve stayed tight with no creaking or other issues and the pedal and spindle inserts are still solidly in place (an issue that has plagued a lot of carbon cranks from various brands over the years). Their factory-applied protective film has also staved off any notable wear from heel rub. The original crank boots that TRP supplied were pretty loose-fitting and easy to dislodge, but they’ve got an updated design that fits much better. Reach out to them if you’ve got an early set of cranks and want to snag the updated boots.

TRP also does a commendable job of offering replacement individual parts for both the shifter and derailleur, in an easily accessible spot on their website. They don’t list every single possible piece, but a lot of the bits that are either potential wear items or can possibly damaged in a crash are available, including the derailleur inner cage plate and clutch assembly.

Who’s It For?

This feels hard to answer precisely — the Evo 12 drivetrain works really well, but so do the similarly-priced options from the big S-brands. At least for my taste, the biggest way the Evo 12 sets itself apart is its shifter ergonomics / feel — it’s genuinely my favorite of the bunch, though that’s a wildly subjective take. But if you want a high-end mechanical drivetrain and have been put off by SRAM or Shimano for one reason or another — be it SRAM’s gearing steps or clutch durability, Shimano’s stiffer-feeling shifters, or whatever else — the Evo 12 is a genuinely worthwhile option.

Bottom Line

Making a drivetrain go toe-to-toe with SRAM and Shimano’s high-end mechanical offerings is a tall order, given how much experience those brands have, and how completely they dominate the high-end MTB drivetrain market. But on their second try, TRP has pulled it off.

The Evo 12 drivetrain isn’t perfect (nor are its competitors), and while it’s not categorically better than what SRAM and Shimano have on offer, it’s a legitimate competitor to them — that’s a real achievement by TRP.